Pull up a chair and maybe grab a notepad. You might want to hold onto your coffee mug with both hands for this one. We're going to talk about something that sounds ripped straight from a comic book, but it's actually being seriously discussed by some of the smartest people on the planet, people who do math that would make our brains hurt.

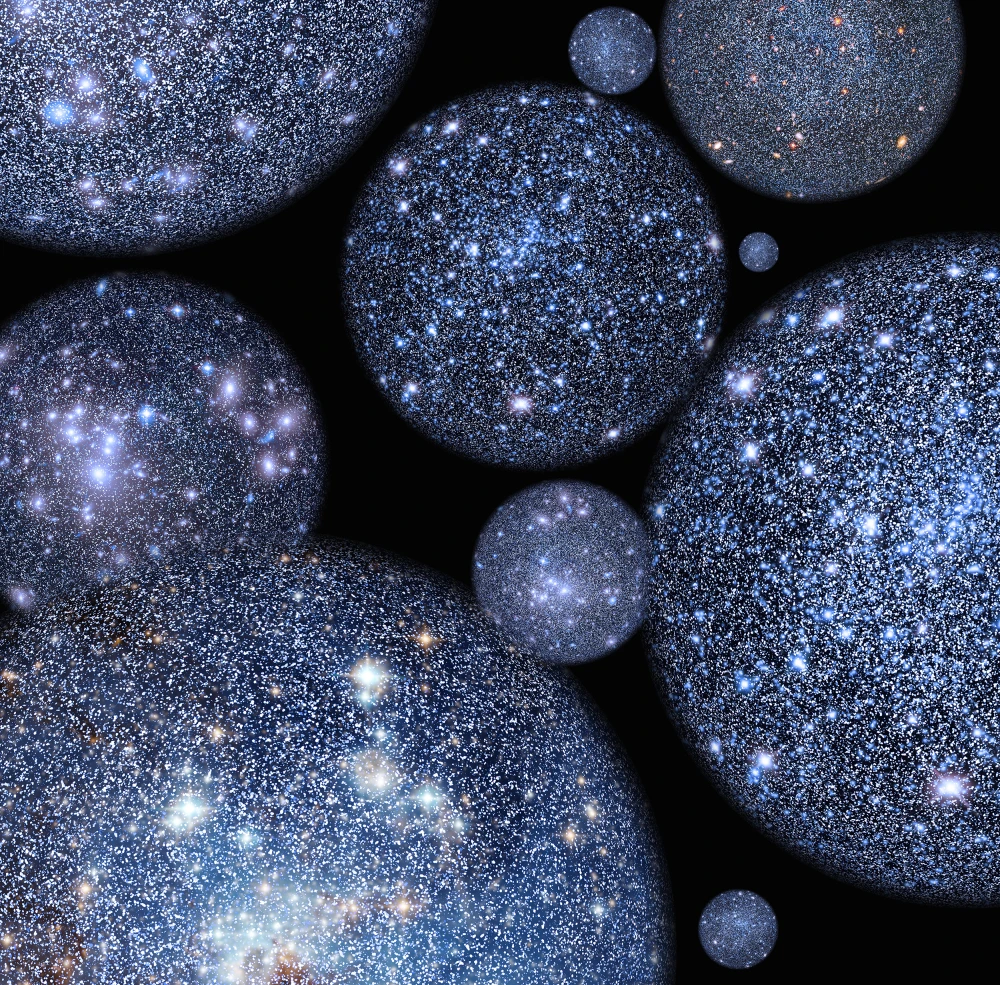

We look up at the night sky and think, "Wow, that's big." But what if all of it, every star, every galaxy, every black hole, every weird thing happening on Earth right now, was just one single, solitary bubble in an infinite, bubbling cosmic ocean?

That's the Multiverse. And trust me, once you truly start unpacking the reasons why scientists are taking it seriously, you'll never see reality the same way again.

Why Even Go There? The Cosmic Fine-Tuning Problem

Steven Weinberg

Nobel laureate in Physics, theoretical physicist

Martin Rees

Britain's Astronomer Royal, cosmologist

First off, why are top physicists like Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg or Britain's Astronomer Royal, Martin Rees, even thinking about this? It's not for fun. It's because our universe appears to be balanced on a cosmic knife-edge. It's suspiciously perfect. This is called the Fine-Tuning Problem.

Think of it like a cosmic control panel with a row of dials. These dials represent the fundamental constants of nature:

- The strength of gravity (G)

- The mass of an electron

- The strength of the force that holds atoms together (the strong nuclear force)

- The speed of light (c)

- A particularly strange one called the Cosmological Constant (Λ), which affects how fast the universe expands

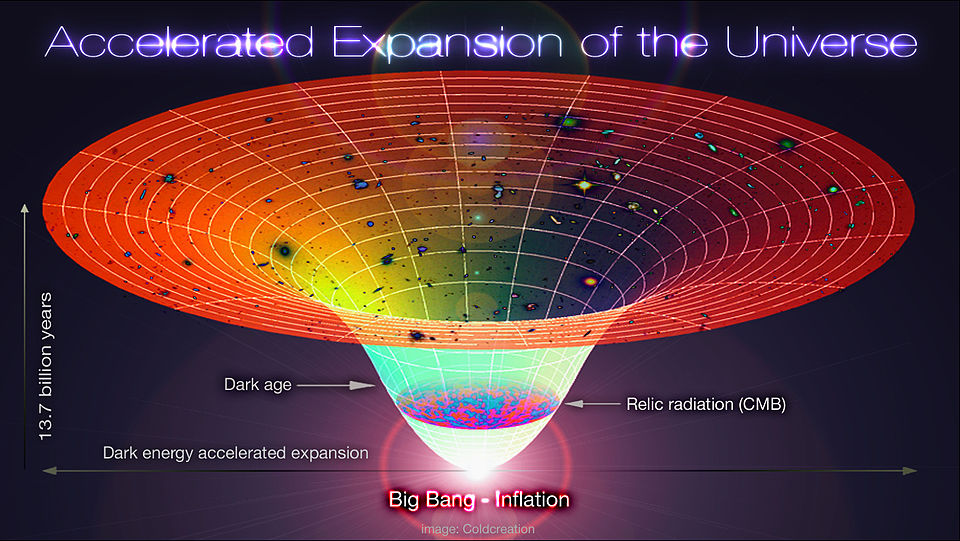

The cosmological constant, once thought to drive only late-time expansion, may have quietly shaped the universe from its earliest moments.

Design: Alex Mittelmann, Coldcreation

Here's the mind-bending part: every single one of these dials is set to an unbelievably precise value that is required for a universe to support any kind of complexity, let alone life.

If you were to nudge the dial for the strong nuclear force just a tiny bit, stars would either be unable to create elements heavier than hydrogen, or they'd burn out in a flash. If you tweaked gravity slightly, galaxies never would have formed, or they would have immediately collapsed back on themselves. The odds of our universe getting these values by chance are so small it's almost unbelievable.

So, this leaves us with a few deeply weird possibilities:

The Absurdly Lucky Universe: We just won a cosmic lottery. It just happened that way. End of story. This is an answer that most scientists find pretty unsatisfying.

A Deeper Theory: There's some undiscovered "Theory of Everything" that shows these values have to be what they are for purely mathematical reasons we just don't get yet.

The Anthropic Principle: Here's where things start getting weird and a little philosophical. The Anthropic Principle is the idea that the universe must have the properties necessary to allow observers (like us) to exist, simply because we're here to observe it.

Now, I know this Anthropic Principle can sound a bit circular and kind of confusing. I definitely didn't get it the first time either. So let's slow it down with a couple of simple examples.

First, imagine this: you're baking cookies, and one of them comes out of the oven, looks around the tray (just roll with it), and says: "Wow, this baking tray is the perfect shape for me. It must've been made to fit my cookie body!"

But here's the thing that's backwards. The cookie fits the tray because the tray shaped the cookie, not the other way around. The cookie only thinks the tray fits it perfectly because it was baked to match the tray's conditions.

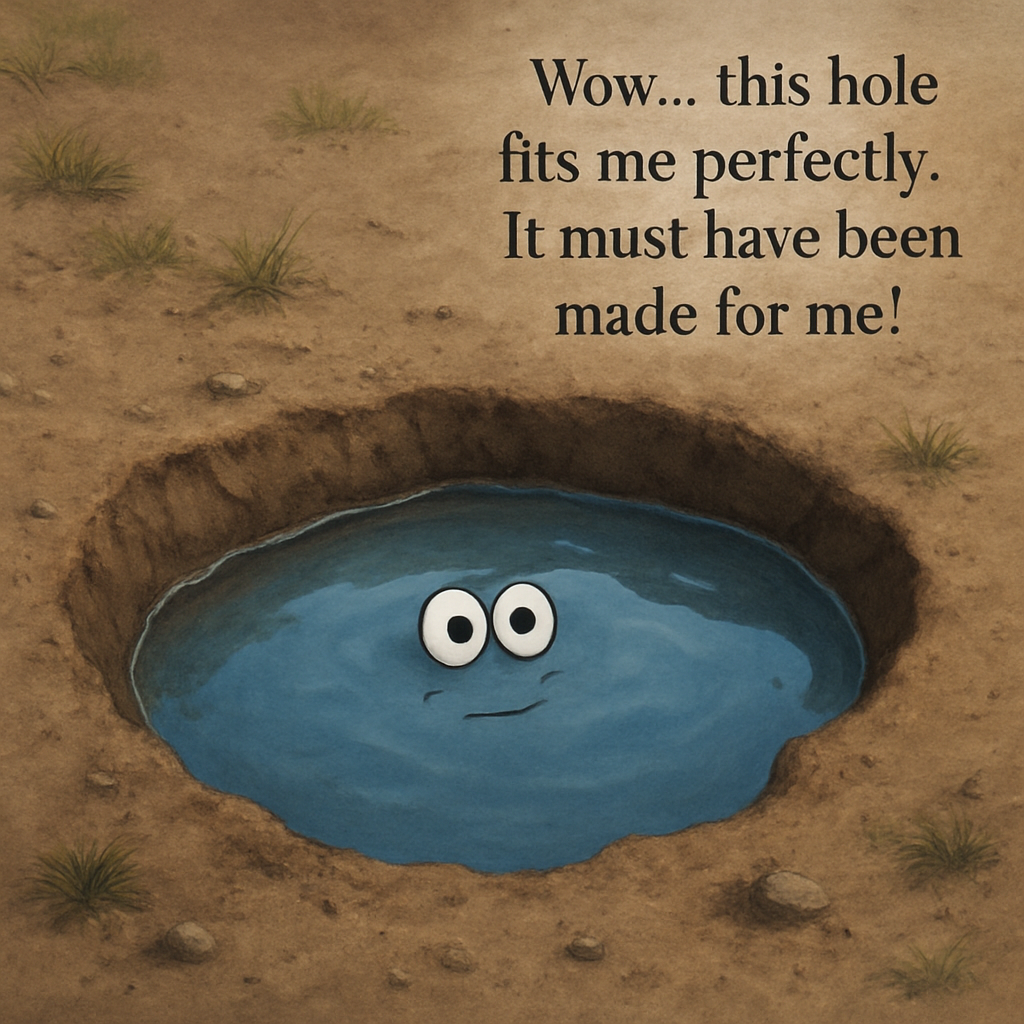

Now let's level it up a bit with a famous analogy from Douglas Adams (who gave us The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy). Imagine a puddle of water suddenly becoming self-aware and thinking, "Wow, this hole I'm in is shaped perfectly for me! It fits every curve of my body. Surely it was made for me!" But of course, that's backward. The puddle isn't in a specially designed hole; it simply takes the shape of whatever hole it finds itself in. If the hole were different, the puddle wouldn't exist in its current form. It fits because it had to.

That's the heart of the Weak Anthropic Principle. We observe a universe that's perfectly tuned for life not necessarily because it was made for life, but because only in a universe like this could life (and questions about the universe) even exist in the first place.

But there's a spicier, more controversial version called the Strong Anthropic Principle (SAP). This version goes a step further and suggests that the universe, for some unknown reason, had to have properties that would allow life to develop at some point. This doesn't mean it was designed by a creator, but it hints that there might be some underlying principle of physics we don't understand that makes life an inevitable outcome of the cosmos. It's a much bigger claim and one that makes many scientists uneasy, but it's a fascinating philosophical puzzle.

The multiverse is the most popular scientific explanation for all this. If you have an infinite number of universes (holes of all different shapes), it's no longer a surprise that a few of them (puddles) happen to be just right for life to exist.

The Different Flavors of Multiverse (Choose Your Mind-Melt)

Max Tegmark

MIT physicist, multiverse theorist

This is where it gets really wild. Physicists, like the brilliant Max Tegmark, have sorted the different multiverse ideas into levels, and each one gets weirder than the last.

Level I: The Really, Really Big Neighborhood

This one is the easiest to get your head around because it doesn't require any new physics. It just requires that space is infinite. If space goes on forever, then it has to start repeating at some point. It's basically a mathematical guarantee. Our observable universe is a giant sphere we call our Hubble Volume. In an infinite space, there are an infinite number of these Hubble Volumes. So, somewhere out there, incredibly far away, there's another Hubble Volume that is identical to ours. And another you.

Level II: The Cosmic Bubble Bath

Alan Guth

MIT physicist, cosmic inflation pioneer

Andrei Linde

Stanford physicist, eternal inflation theorist

The leading theory for the universe's first moment is Cosmic Inflation, first developed by physicists like Alan Guth and Andrei Linde. The "eternal inflation" model suggests this inflation never completely stopped. It's a constantly expanding, bubbling sea of energy. Every now and then, a "bubble" pops into existence, and BOOM! A Big Bang happens inside it, creating a new universe. Our universe is just one of those bubbles. And the laws of physics could be set randomly in each bubble, which perfectly explains the fine-tuning. This whole process is described by the deep math of how the universe works, like the Friedmann Equation:

The Friedmann Equation describing cosmic expansion, where H is the expansion rate, G is gravity, ρ is density, k describes geometry, and Λ is the cosmological constant.

Here, H is the expansion rate, G is gravity, ρ is the amount of stuff, k describes its shape, and Λ is that strange Cosmological Constant. Each bubble could have different values, leading to a wildly different universe.

Level III: The One That Truly Messes With Your Head

Hugh Everett III

Physicist, Many-Worlds Interpretation founder

This idea, the Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI), comes from quantum mechanics, proposed by Hugh Everett III. It says that when a quantum particle has multiple possible outcomes, it doesn't pick one. Instead, the universe splits into multiple branches, one for each outcome. This means that for every choice you thought you made, there's a branch of the multiverse where another you made a different choice. The universe doesn't choose; it does it all.

Level IV: The Deep End of the Pool

This is Max Tegmark's own Mathematical Universe Hypothesis (MUH). It's the most extreme version. It suggests that any universe that can be described by a set of mathematical rules that don't contradict themselves is real. If the math works, it exists. This makes our universe just one "book" in an infinite library of all possible mathematical worlds.

Wait, So What About Aliens?

If any of this is true, the idea of aliens just being "little green men from another planet in our own universe" seems almost old-fashioned, doesn't it? The possibilities become truly mind-boggling. We could be talking about beings made of pure energy or life that evolved in a universe with completely different physical laws. Are we living in a simulation run by some cosmic being in another universe? Based on these theories, it's a perfectly logical, if spooky, question to ask. But the sheer variety of what 'alien life' could actually look like, from simple organisms on icy moons to the god-like engineers of entire universes, is a deep and fascinating topic all on its own.

Let's Be Real for a Second

Okay, let's bring it back to Earth for a moment. It's exciting to get carried away, but here's the simple breakdown:

Solid Science: The theories that lead to these ideas, like General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics, are supported by a ton of evidence. The Fine-Tuning Problem is a very real puzzle.

Educated Guesses: The existence of bubble universes or branching timelines are logical next steps from those theories, but they are unproven for now.

Deep Speculation: The idea of a purely mathematical reality or traveling between universes are amazing concepts, but they are as much philosophy as they are physics right now.

So, are we alone? The multiverse suggests the answer is a resounding "no." But it also changes the question entirely. The real mystery isn't just "what else is out there?" but "what else is even possible?" And if the multiverse opens the door to infinite possibilities, it also cracks open the question of aliens not just whether they exist, but how strange, ancient, or wildly different they might be. Explore Aliens and the Multiverse →

It's a thought that leaves you humbled and amazed, looking up at the sky and realizing that reality might be infinitely bigger, weirder, and more wonderful than we ever imagined.